Divesting shares: does it work?

Financial Times

Calls for divestment are once again reverberating across the globe. Does it work?

Selling holdings in companies to effect change — be it political, environmental or social — bumps up the targeted companies’ cost of capital. It adds what Harvard Law School calls “voice”, driving change that reverberates through mass media and high-profile institutions, and ultimately defenestrating the powerful lobbying might of perceived miscreants.

So runs the theory. Cases backing it up include the kneecapping of Big Tobacco in the western world and the (official) end of apartheid in South Africa. The latter came after 155 North American colleges and schools divested $719bn — over $2tn in today’s money — of relevant holdings.

In practice, things are less clear cut. For one, divestment seldom occurs in isolation and only works as part of a bigger arsenal, comprising sanctions, political will and withdrawal of other financing, such as bank debt. Big Tobacco’s whammy included multibillion dollar lawsuits, government clampdowns on advertising and more health conscious populations.

Divestment, which as cynics point out is simply switching ownership to disinterested parties, is itself a long game. Guardians of assets, be they endowments, pensions or mutual funds, would be doing their investors a big disservice by dumping targeted stock wholesale: instead they plot lengthy and staggered exits, details of which are kept carefully under wraps.

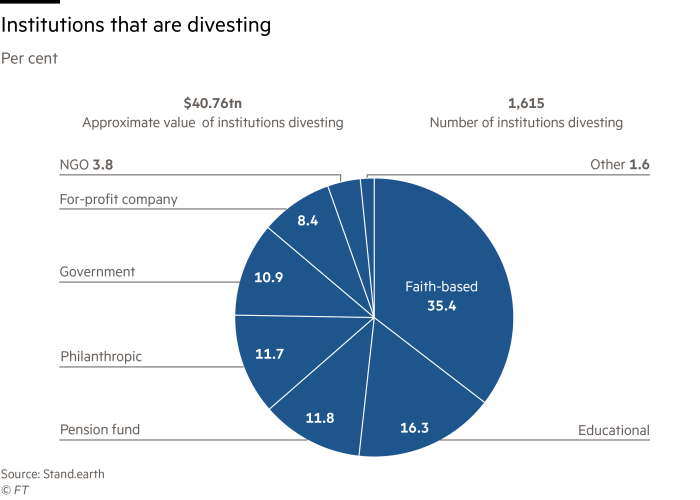

Take fossil fuel divestiture, which boasts some hallmarks of success. There are now 1,600-plus institutions, sitting on an aggregate $40tn-plus of assets, according to Stand.earth which runs a database of fossil fuel divestment commitments. Conservatively, some $1tn has moved out of — or is pledged to exit — the sector in the past 13 years, estimates Stand.earth’s Richard Brooks.

There have been high-profile sellers, like the Church of England whose money managers plan to jettison oil and gas majors not already excluded from its £10.3bn portfolio. “It is our duty to protect God’s creation,” said the Most Revd Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury and chair of the Church Commissioners for England.

But even big voices go only so far when other factors are at play: oil, whose fortunes are in any case cyclical, saw prices rise on the back of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Far from denting the cost of capital, share prices of traditional energy stalwarts have comfortably outperformed renewables over the past three years.

Hence the carrot and stick trade to redeploy funds into sustainable energy. The New York State Common Retirement Fund has committed

The full article is available here. This article was published at FT Markets.

Comments are closed for this article!